Ebenezer Oliver Grosvenor - The Man and His Mansion

The western frontier exerted a powerful pull on young men eager to make their fortune and even pick up a little fame in the process. Ebenezer Oliver Grosvenor came from a good family in Stillwater, New York and was well-educated at the prestigious Cittenango Academy until he was 15 years old, after which he clerked in a store for two years. In 1837, at 17 years of age, he was a man. He followed an older brother to Albion, Mich., probably taking the Erie Canal and the Chicago Military Road, formerly known as the Sauk Trail. Ebenezer clerked in his brother’s store and then moved to Monroe in 1839, where he was the assistant bookkeeper for the State Railroad Commission, which was then constructing the Michigan Southern Railroad.

The accounts written about successful men of that time were typically effusive with praise about what upstanding, contributing citizens they were. It’s hard to separate the flowery language from the true character of the man, but deeds can be a window into power and influence. Although Ebenezer was only with the railroad for a short time, he was instrumental in helping establish its route through Hillsdale County, most importantly, through Jonesville where he ultimately settled. As such a young man, he must have had a manner and personality that inspired confidence and belief in the wisdom of his suggestions. His future involvements in politics from the local to the state level certainly reflected an ability to persuade others to follow his lead.

At any rate, Ebenezer landed in Jonesville in 1840 when it was little more than a hamlet with a stagecoach stop on the Chicago Military Road. He clerked in the dry goods store of H.A. Delavan until 1844, when he opened a general mercantile with R.S. Varnum. There were a succession of partners until 1869, when he sold his share of the store. During his time in the mercantile he demonstrated his honesty and reliability to the area farmers from whom he purchased produce by always paying in cash.

From his involvements, Ebenezer seemed to be a rainmaker. He bought several hundred acres of land, was the first Treasurer of the Jonesville Cotton Manufacturing Company and engaged in an important building project along Chicago Street after a fire in 1849 that destroyed a good portion of the downtown area of Jonesville. Fires were rampant in the age of wood-heated wooden buildings. Ebenezer and four others replaced the fire-damaged buildings with a two-story brick block about 100 feet long. As well as coping with the aftermath of fire, he helped organize the Protection Company, No. 1, a fire company that began with the purchase of a fire truck (that was originally housed in George Munro’s barn).

Ebenezer’s standing and contribution to Jonesville continued. He established the Exchange Bank of Grosvenor and Company in 1854 (which was reorganized in 1891 as the Grosvenor Savings Bank). He became a stockholder in the railroad and at least two insurance companies. He was a busy guy who also was keen to make his mark on local politics. He was a Township Supervisor and a member of the Jonesville School Board for 41 years.

But bigger political fish were still to fry. In 1858 he was elected to the Michigan State Senate. By 1861 he was the president of the military contract board and came to the attention of Gov. Austin Blair, who tapped him to join his staff as a Civil War colonel. Ebenezer returned to the State Senate in 1862, but became the Lt. Governor of Michigan during the first term of Gov. Henry Crapo. From 1867 to 1871 Ebenezer applied his skill as a money manager as State Treasurer of Michigan, and he joined the Board of State Buildings Commission in order to build the new capitol in Lansing. Turning to the man who would also design his magnificent mansion in Jonesville, Elijah E. Meyers, Ebenezer managed the unheard-of accomplishment of coming in under budget on the capital, returning $15,110.46 to the State Treasury. (This remarkable financial skill was duplicated in Jonesville when Ebenezer led the building committee of the Presbyterian Church, which was dedicated free of debt in 1878.)

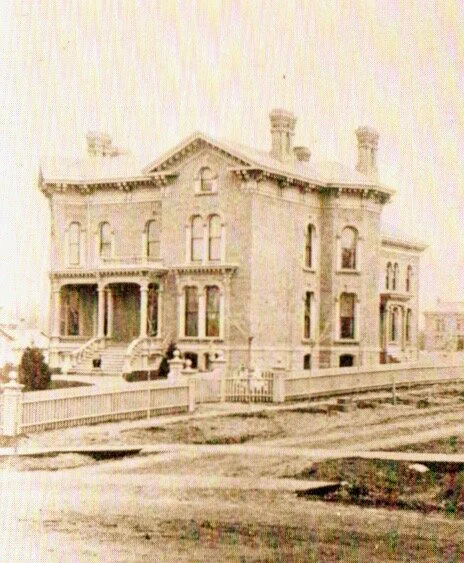

In 1844, the same year he went into business with Varnum, Sally Ann Champlin became his wife. With their surviving child, Harriet, already married to Charles White in 1872, the Grosvenors hired Elijah E. Meyers to design and build a home for them (which cost a little under $40,000). And, oh, what a home it was! Sitting majestically on a hill to the east of the town of Jonesville, its beauty was exceeded only by the ultra-modern comforts it contained. Stunning in its elegance, the home was full of craftsmen-carved wood of walnut, butternut and English oak. Two-tiered wooden shutters graced every window except the kitchen. It was centrally heated by a double furnace, with a gas generating plant providing power for lighting, a double-brick wall construction, 14’ ceilings on the first floor and 12’ ceilings on the second. Speaking tubes throughout the 32-room home eliminated the need to find each other by yelling, and its water system defined comfort. A two-man pump took water from cisterns to the attic, where it was stored in a lead-lined tank (a material that was not the best choice, actually). There, with a gravity-feed, two fully equipped bathrooms with flush toilets as well as sinks in each of the five bedrooms were supplied with hot and cold running water. The master bedroom on the first floor also featured his and hers closets, surely a forward-thinking idea. The only nod to cost savings was with the unheated servants quarters.

When Ebenezer and Sally died within four months of each other in 1910, their grandson Charles White had already become the president of the reorganized bank, then known as the Grosvenor Savings Bank. Charles’s brother, David, moved into the mansion with his wife, Thalla, and daughters. It remained in the hands of generations of Whites until the early 1950s, when many of the furnishings were sold along with the home. A succession of renters and owners continued until 1977 when, sparked by the Bicentennial of our country, the Hillsdale Heritage Association led by Christine Rowley initiated a campaign to purchase it. Private donations, memorials and area industries combined to amass $50,000 to buy the house, with an additional $12,325 to purchase some original furnishings from other places.

At the Sesquicentennial of Jonesville in 1978, a State Historic Marker was unveiled, designating the Grosvenor House Museum as a member of the National Register of Historic Places. The home was carefully restored with original and donated furnishings that matched the period and social level of the original. To this day, the Board and membership of the Grosvenor House Museum keep alive the name of Ebenezer Oliver Grosvenor through tours and events at the home, while also making it available for rent for private events.

JoAnne P. Miller